Polymorphism via dispatch¶

(IN DRAFT)

Note: This section is expected to supercede the discussion on objects.

When writing our procedures/functions in a programming language, we deal with different data structures and entities such as files, network sockets and processes. For any given system, a number of such entities serves as its “API” or “Application Programming Interface”. If each of these entities were to be transacted with using its own vocabulary, it will become very hard for programmers to retain the vocabularies necessary to work with a practical subset of these entity types in working memory so they act of programming is both efficient and reliable.

Thankfully, many of these entities can be worked with using a much smaller set of “verbs” using which programmers typically chunk their thinking about them. For example, both hash-tables and vectors in Racket offer the notion of associating a value with a key. Only, in the case of hash-tables, the key can be anything “hashable” whereas in the case of a vector, the key must be in the range \([0,N)\). However, the act of getting a value associated with a particular key can simply be thought of across all such data structures using the verb “get” and similarly the setting of a value against a particular key can be thought of using the verb “set”.

For an analogy, consider the Harry Potter world and Hermione Granger’s timely use of the spell “Alohamora” to open a lock. Suppose that in the wizarding world, each kind of lock required a different spell to be learnt to open it – “Alohamora Big One”, “Alohamora 42”, “Alohamora Locksmith & Sons Tiny 2021 edition” and so on – wizards might give up pretty soon. But we have a hint here – that the word “Alohamora” suggests that the lock needs to be opened, and the ones programming these locks can determine what to do when the lock hears the spell “Alohamora”, instead of making custom spells for it. This would then obviously be preferrable for wizards (and students!) since they would then need to remember far fewer spells overall to be effective in their world.

Racket library functions kind of work as though they were in that complicated

world of spells. In Racket, though you’ll find procedures named according to

such common vocabulary, each data structure carries its own set of procedures

to work with it. So vectors come with vector-ref and vector-set! and

vector-length, and similarly hash-tables have hash-ref,

hash-set! and hash-count. If we were to invent another data

structure, say, treemap, then we’ll have to expose yet more procedures

named treemap-ref, treemap-set! and treemap-length that will do

analogous things with tree maps. If we choose completely different vocabularies

– say, treemap-search-and-retrieve, treemap-find-and-replace and

treemap-count-entries – we’d place a huge cognitive burden on programmers

who’d want to adopt our new data structure since they cannot reuse their

vocabulary in the new context.

What if we could simply say ref, set! and length and when we

introduce a new data structure, be able to declare how these verbs should work

with it at that point? That way, if we have a vector v, we reference its

k-th element using (ref v k) and if we have a hashtable h and a key

k, we can get its associated value using (ref h k) as well, instead of

(hash-ref h k). It is quite evident that the cognitive burden is lower for

such a unified concept of “ref-ing” a value. This “reuse of verbs” with

different objects is the essence of “polymorphism”.

While doing this makes for concise code while writing, we also notice that when

reading code, (ref h k) tells us very little about h than “something we

can call ref on”, whereas (hash-ref h k) is amply clear. This is part

of the reason for that design choice to be explicit in the Scheme/Racket

languages. The goal of a program is only partly to instruct machines (such as

“locks”) but equally to communicate “how to” knowledge to other humans.

Terminology

Such a multi-purpose definition of a verb like ref and set! is

referred to in programming languages as “polymorphism” and the verb is said

to be “polymorphic” over a collection of types.

Exploring through “property lists”¶

We’ll explore the design space of object oriented programming languages through a basic structure called a “property list”, which we’ll assume that our interpreter has access to at any point (i.e. globally).

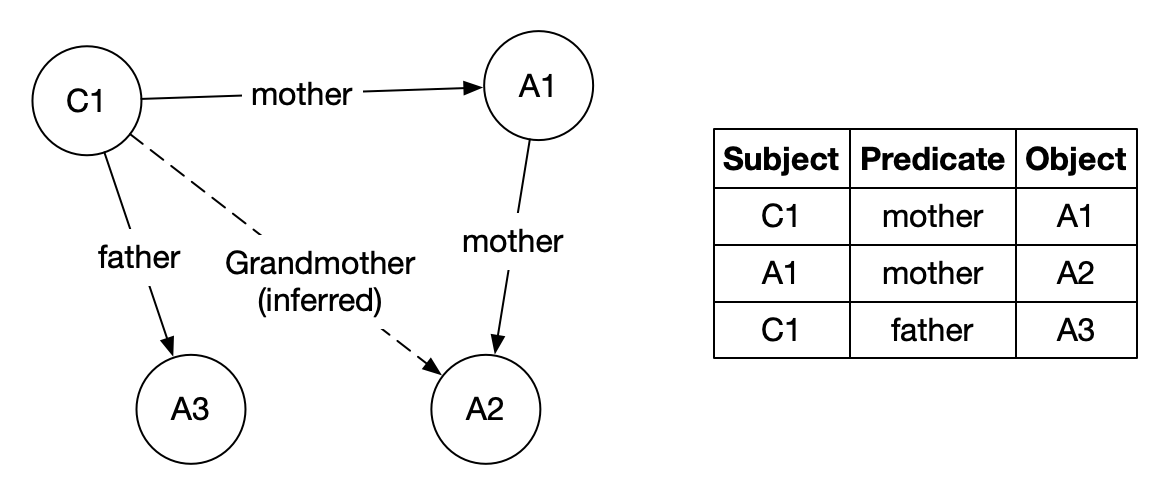

A property list is a simple structure that asserts connections between

“subjects”, “objects” (not to be confused with “object” in the OOP sense, but

linguistic “object”) via “predicates”. For example, the triple (Tri

child23 'mother adult42) establishes that the 'mother of

child23 is adult42. This relationship can be thought of as a

labelled arrow from the child to the adult. This way, arbitrary graphs can be

represented using such a triple store.

Fig. 5 A triple store can be seen as a graph.¶

We’ll now model several “object orientedness” ideas based on such a triple store. Note that this is not to say that such a triple store is what is backing the various object systems. Far from it. We’re using the plist as a way to explore the design space and options we have when we’re interested in minimizing the vocabulary we use to program.

In this chapter, we use the plist.rkt module which you can include

using (require "./plist.rkt") from your own code.

We’ll assume that we’re working with a global plist. Furthermore, we’ll dispense with implementing it in our language’s interpreter and do it in plain Racket, since the translation process should now be familiar and simple to perform.

(require "./plist.rkt")

(define plist (make-plist))

(define (setprop! thing key value)

(set! plist (plist-assert plist think key value)))

(define (getprop thing key)

(let ([values (plist-find plist thing key #f Tri-obj)])

(if (empty? values)

(begin ; What do we do here?

)

(first values))))

In the above implementation, we’re assuming that the plist only holds

a single value for a given thing-key combination. We’ll relax

this condition later. For now, note that this is a design space option

available.

We’re now faced with the problem of determining what to do when an associated value for a given thing and key is sought for in the plist and one is not present. We’ll choose a general way to deal with this by passing a handler function.

(define (error-on-not-found thing key)

(error 'key "Property ~s of ~s is not found" key thing))

(define (getprop thing key [not-found-handler error-on-not-found])

(let ([values (plist-find plist thing key #f Tri-obj)])

(if (empty? values)

(not-found-handler thing key)

(first values))))

We’ll also define a simple structure to make object references.

We’ll give it an id field so when printing out an object, we

know its name. There is no other significance to this id field.

(struct Obj (id) #:transparent)

A prototype based object system¶

The Self language pioneered the idea of a prototype based object system.

Although historically this came after the class based system introduced by

Smalltalk as a response to the problem of prematurely having to determine

an application’s architecture based on “classes” that aren’t necessary known

up front and will be discovered along the way. In other words, the prototype

based system was seen as a way to evolve software as requirements come in

during its development. The object system in JavaScript is based on these

ideas developed in Self.

So, what is an “object” in such a system in the first place? In such a prototype based system, an object is simply a collection of named properties and “methods”. A “message” to an object involves a “message name” (a.k.a. “selector”) and some additional arguments. When a message is “sent” to an object, it looks up a corresponding method (in a table), which is a procedure and calls the procedure with the given message arguments. Methods also need to get a reference to the object as well, so they can access other properties and methods they need.

Objects and state

Note the change of language we’re faced with when looking at such “objects” – in particular, we’re using an imperative language as though the object has some internal storage that we can only influence through message passing and it is free to do anything with that internal data in response to messages. This “state encapsulation” is a significant by product of object think and there would be no reason to choose a dominantly object based design for a system unless it requires and exploits such state encapsulation to simply using and reasoning about the system.

So we’ll make a simple function to which we can give a list of keys and values (including method procedures) and get an object reference that is associated with those properties and methods.

(define (object id . kvs)

(let ([obj (Obj id)])

(let loop ([kvs kvs])

(if (empty? kvs)

obj

(begin (setprop! obj (first kvs) (second kvs))

(loop (rest (rest kvs))))))))

With that definition in hand, we can do the following -

(define dog1

(object 'puppy

'color 'brown

'bark (λ (self) (displayln "Yelp!"))))

(define dog2

(object 'adult

'color 'black

'bark (λ (self) (displayln "Woof Woof!"))))

(define cat1

(object 'siamese

'color 'grey

'bark (λ (self)

(error "I don't bark! Am I a dog?"))))

> (getprop cat1 'color)

'grey

> (getprop dog2 'color)

'black

Now, what does it mean to send an object a message? In our case, we’re modelling “message passing” as “method invocation”. So we need to take the message name, look it up in the property list against the object, and call the function associated. For now, we’ll leave the “no such method” condition as an error.

(define (get obj propname)

(getprop obj propname

(λ (obj propname)

(error "Placeholder. Property name not found."))))

(define (send obj message . args)

(let ([method (get obj message)])

(if (procedure? method)

(apply method (cons obj args))

(error "Method must be a procedure"))))

Now we can make our animals make noises -

> (send dog1 'bark)

Yelp!

> (send dog2 'bark)

Woof Woof!

Note that the objects are doing something different though both have been asked to “bark”. This is pretty much the whole value behind object oriented programming. Objects are able to do this because they encapsulate state in the form of properties.

Now, notice that the cat1 object errors out when asked

to bark. However, we may think of both cats and dogs as

“four legged animals”. Let’s make an animal object that

represents this idea -

(define animal (object 'Animal

'num-legs 4))

Now, we’d like to have our cats and dogs respond to a request

for 'num-legs with 4. We can of course add these properties

to each of those objects, but that feels redundant.

Here is where the “Placeholder” gains importance. We left open the question of what to do when a property is not found. We can now exploit that gap by asking another linked object for the property. But which other object? For that, we can look it up in the property list.

(define (get obj propname)

(getprop obj propname

(λ (obj propname)

; Note the recursive call to 'get'

(get (getprop obj 'super

(λ (obj superkey)

(error "No such parent")))

propname))))

We did something interesting there. We first try to look up a “super” property

of the object, which we expect to be defined to another object. If we find one,

we then ask that object for the property. If such a “super object” doesn’t

exist, the getprop will error out. But if it does, it will be as though our

object gained the properties of that “super object”. Now, when getting the

property of the “super”, we do it recursively so that if that “super” also

didn’t have that property or method, we look up its “super” and so on until

either the property/method is found or it errors out.

Note that we’ve again left a placeholder for the condition when the “super” of an object cannot be found. We’ll return to this choice point later. First let’s see what this mechanism buys us for our animal farm.

(setprop! dog1 'super animal)

(setprop! dog2 'super animal)

(setprop! cat1 'super animal)

> (get dog1 'num-legs)

4

> (get cat1 'num-legs)

4

We can now also add a method dynamically to animal and all the

animals will automatically get it.

(setprop! animal 'walk

(λ (self num-steps)

(setprop! self 'steps-walked

(+ (getprop self 'steps-walked (λ (self key) 0))

num-steps))))

> (send dog1 'walk 3)

> (get dog1 'steps-walked)

3

> (send dog1 'walk 5)

> (get dog1 'steps-walked)

8

It’s tiring¶

Now, imagine the process we went through just got bigger with many

tens of methods and properties. Every time we make a new object – an

animal – we have to define these properties on each of them. The

ability to delegate commonly accessed methods to such a “super”

object like we just did is therefore a boon since we can just accumulate

those common methods in that “super” object and make the other objects

just reference it via their 'super property.

This is the essence of how “classes” are modelled in prototype based object systems. The “super object” of an object is known as the object’s “prototype”. In such systems, a prototype that also has a method that can construct “instances” of it is referred to as a “class”.

Such prototype based systems do not really distinguish between the notions of

“object methods” versus “class methods”, since these “classes” are themselves

objects and when you send a message via the object, the method actually affects

the object in question and not its class, unless you make the class the target

of the message send. This is due to the methods taking the object as their

first argument usually named self, as with Python or this as with

JavaScript.

Class methods¶

In order to distinguish between “class methods” (methods that operate on the class) versus “object methods” (methods that operate on the object that inherits properties and methods from the class), we therefore need to make that distinction available in the message sending procedure.

So far, we only added the self argument. In the send procedure, we

first lookup the message in the object hierarchy and then invoke the method on

the object. If we separate the two, we gain the ability to use the methods in

one object and apply then on another. To keep the generality, we need to

augment our method argument list with the object we use to lookup the method as

well so that the method can do what it pleases with that information. The

effect of this is only relevant when we have deeper and/or broader class

hierarchies though.

(define (send/super super obj message . args)

(let ([method (get super message)])

(if (procedure? method)

; Note the change in protocol for method invocation

; which now takes an additional "super" argument.

(apply method (cons super (cons obj args)))

(error "Method must be a procedure"))))

; Note that in class-based object systems, method lookup

; starts with an object's class and not the object itself.

; So we need to lookup an object's ``'isa`` property and

; and invoke ``send/super``.

(define (send obj message . args)

(apply send/super (cons (getprop obj 'isa)

(cons obj (cons message args)))))

(define dog1

(object 'puppy

'color 'brown

'bark (λ (super self) (displayln "Yelp!"))))

(define dog2

(object 'adult

'color 'black

'bark (λ (super self) (displayln "Woof Woof!"))))

(define cat1

(object 'siamese

'color 'grey

'bark (λ (super self)

(error "I don't bark! Am I a dog?"))))

(define animal

(object 'Animal

'num-legs 4

'walk (λ (super self num-steps)

(setprop! self 'steps-walked

(+ (getprop self 'steps-walked (λ (self key) 0))

num-steps)))))

So what new capability does doing this give us? Within a method, we can now delegate a part of the functionality to the “super” if we wish. For example, if we want to make a custom “walk” method for the cat that depends on whether it is tired, we can do this -

(setprop! cat 'tired #t)

(setprop! cat 'walk

(λ (klass self num-steps)

(if (get self 'tired)

(error "No energy for a walk. Go away. Meeeow!")

(send/super (get klass 'super) self 'walk num-steps))))

Notice how the cat delegates to its super the ability to walk when it

is able to, but errors out otherwise. Under normal method invocation,

klass will be the same as self, but we can choose differently,

just as the method does when turning around and invoking the parent

implementation directly, but without changing the target object.

Classes and Types¶

We saw how the concept of a class arises in a prototype based object system – mostly to collect a group of related methods that apply to a set of objects that are said to be “instances” of the same idea. In our example, the dogs and the cat were instances of “animal”.

Due to this correspondence, such a delegate object (which we called “super”) can be thought of as the “type” of the object. Languages like C++ and Java which are class based often take this approach. In these languages, a class acts like a factory for objects which imbues the objects it creates with a consistent set of properties and methods.

We can pretty much use the same get algorithm with naming the

property lookup class instead of super and it will start

to look like a class based object system. In such systems though,

the relationship between an object and its class is deemed to be

an “is-a” relationship and it is the class which has a hierarchy

and not the object. When an object is created, it is created with

“slots” for its properties and the methods are all grouped within

the class. The object itself does not maintain a table of methods

but delegates method lookup to its class. We can model this structure

like below –

(define (get thing propname)

(getprop thing propname

(λ (thing propname)

(get (getprop thing 'super) propname))))

(define (send obj message . args)

(let ([klass (getprop obj 'isa)])

(apply send/super (append (list klass obj message) args))))

Uniformity considerations¶

We saw that “pure” OOP systems tend to say “everything is an object” and that “everything happens via message passing”. This includes languages like Smalltalk, Self and Ruby. Here is, for example, how such a system might handle branching on a condition.

(setprop! 'True 'if:else: (λ (ctxt obj thenblock elseblock)

(thenblock)))

(setprop! 'False 'if:else: (λ (ctxt obj thenblock elseblock)

(elseblock)))

So the result of a boolean computation is a singleton instance of one of the

“classes” named True and False, which dispatch on the 'if:else:

message on one or the other branch depending on which instance received the

message.

Other control constructs are also cleverly constructed based on the fundamental

notion of a “block” - which plays the role of a lambda function in OOP

languages like Ruby and Smalltalk, and are “ordinary” first class functions in

languages like JavaScript and Python. For example, a block object could have

a method named whileTrue: which takes another block and runs it repeatedly

until the target block returns with False.

What about ordinary numbers then? Should we declare each number used in the system to have a property list entry that gives it “class”? That would be terribly wasteful and impractical to do so. So these systems use a few bits in small data types like numbers to tell their types, as an implementation hack. In principle, that is equivalent to having some type checks like below –

(define (get thing key)

(if (equal? key 'isa)

(cond

[(number? thing) 'Number]

[(string? thing) 'String]

[(symbol? thing) 'Symbol]

[(boolean? thing) (if thing 'True 'False)]

[else (getprop thing key)]) ; Errors out if not found.

(getprop thing key

(λ (thing key)

(get (getprop thing 'super) key)))))

Now we no longer have to have individual raw data items like numbers and strings in our property list take just so we can get at their types/classes.

Flipping things around¶

We modelled message passing as method invocation using our send procedure

which we wrote like this (for prototype based inheritance).

(define (send obj message . args)

(apply (get obj message) (cons obj args)))

This puts the object in the centre of the stage and the message plays the role

of something that the object receives and then does something with. We can equivalently

write it as an invoke procedure like below, which puts the message

at the centre of the stage.

(define (invoke method obj . args)

(apply (get obj method) (cons obj args)))

They both do the same thing. But now we can ask an interesting question we might not have asked with the earlier approach – can we now determine which method to call based on the types/classes of more than one object? This situation arises often in scientific computing where “what to do” is often only possible to know when the types of multiple entities are known – such as how to add a complex number to a real number or multiply a real number with a vector, and so on.

(define (gettype obj) (getprop obj 'type))

(define (invoke2 method obj1 obj2)

(apply (getprop method (map gettype (list obj1 obj2)))

(list obj1 obj2)))

In invoke2 above, we’re treating the method as the thing for which

we’re looking up properties against various nominal types (i.e. types by

names). The key is a compound object in this case, a list of two types

(which could be symbols). We can now define methods for concatenating

strings and integers perhaps using this approach –

(setprop! 'add (list 'Number 'Number)

(λ (n1 n2)

(+ n1 n2)))

(setprop! 'add (list 'String 'Number)

(λ (str num)

(format "~s~s" str num)))

(setprop! 'add (list 'Number 'String)

(λ (num str)

(format "~s~s" num str)))

Now we can add number and strings freely. Not that that’s “a good thing”, but we can.

The interesting thing about this approach is that we’re no longer forced to determine whether the code for adding a string with a number should go within the class for strings or the class for numbers! However, it looks like we’ve traded that flexibility for a whole lot of responsibility – that of specifying what procedure to use for potentially N^2 type combinations where N is the number of types in the program. While the problem is not as dire as that, it does get burdensome even dealing with special methods for combining various types of numbers. But the payoff is simplicity for the programmer and that is worth some of the additional work put in to ensure that method names have consistent interpretations across various types.

This approach is also the essence of “multiple argument dispatch”. We can obviously extend this approach beyond just 2 arguments. Julia is a programming language in which this notion of multiple argument dispatch, combined with type inference and just-ahead-of-time compilation is used to generate highly efficient code for scientific computing applications. Julia gets around the problem of having to specify special method implementations for multiple combinations by permitting the definition of generic methods on which type inference at call time can produce concrete types and methods at all the call points and therefore special methods that are consistent with the intent of the verb can be generated on demand. For example, consider the following definition for a “squared distance” -

(define (sqdist dx dy)

(+ (* (adj dx) dx) (* (adj dy) dy)))

If we have implementations for different types for adj, * and

+, this generic way of specifying a computation using those methods

suffices to produce special implementation depending on the context.

For example, if dx and dy happened to be vectors, we can interpret

sqdist to be equivalent to –

(define (sqdist-vec-vec dx dy)

; where vec* acts like a dot product when

; given a row vector and a column vector.

(vec+ (vec* (vec-adj dx) dx)

(vec* (vec-adj dy) dy)))

(define (sqdist-complex-complex dx dy)

(complex+ (complex* (complex-conj dx) dx)

(complex* (complex-conj dy) dy)))

; and so on.

The important simplifying procedure here is that these specialized methods can be automatically generated from one (or more) generic specifications depending on need. [1]

In the above invoke2 procedure, we’re doing dynamic dispatch over multiple

arguments. However, that is not necessary and it is possible to do some of this

analysis at compile time and determine which method procedures to call

statically … which is a huge efficiency boost over determining it for every

pair of, say, numbers over and over again. While Julia can do dynamic dispatch

as a fallback, such a static dispatch is what it relies on for its performance.

In this approach, therefore, a “verb” does not correspond to a single procedure, but to a family of related procedures called “methods” and which procedure to use for a particular call is determined based on the types of the arguments being passed to it.

Miscellaneous considerations¶

Initializing objects¶

In class based object systems, an object is simply configured to refer to its class for the methods and is allocated some memory “slots” to store its properties. Usually though, each kind of object will need to be initialized with the slots containing values that meet some specific constraints of consistency. For example, a “Point2D” object may need to have its “x” and “y” slots be initialized to 0. Such an initialization is done by a designated method in the class called its “constructor”. This “constructor” procedure is run only once at object creation time and is not available for use in the method invocation chain.

(define (new klass . args)

(let ([obj (Obj klass)])

(setprop! obj 'isa klass)

(apply (get klass 'constructor) (cons obj args))

obj))

Note that some languages like Java and C++ enforce different calling forms for

constructors which won’t permit constructor functions to be treated as methods.

This is a language design option and our implementation leaves this enforcement

to later. Python has __init__ methods that serve this purpose that are

valid as ordinary methods. So it is not uncommon to treat a constructor like an

ordinary method as well.

Method not found¶

Earlier, we had a case where we had a failure to lookup a method by name and we errored out. We have another option - to rely on the property list to figure out what to do! For example, if a “method-not-found” procedure is defined for a type, we can call that to determine any dynamic actions to perform.

(define (send obj message . args)

(let ([method (getprop obj message

(λ (obj message)

(get (getprop obj 'super (λ (thing key) #f)) message)))])

(if method

(apply method (cons obj args))

(apply (get obj 'method-not-found)

(cons obj (cons message args))))))